(Some) Lives partially examined, both living and dead

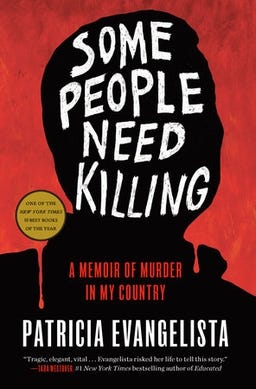

A book review of Patricia Evangelista's Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country

Patricia Evangelista has (arguably) lived a partially examined life.

After all, she has a memoir to show for it.

And, going by the tradition of memoir-writing in this country, she's in good company.

The late senator Jovito Salonga and the late president Cory Aquino's health secretary Alran Bengzon wrote one each. [1]

Published in the latter part of the twentieth century, both memoirs were based on diaries and journals which they kept during messy historical periods of our relatively young Republic.

As a result, the honesty of their accounts remain refreshing almost three decades later.

In his memoir, Salonga said that the Marcoses almost succeeded in transferring US$ 213 million of their ill-gotten wealth into a Viennese bank in mid-1986, just five months after being exiled in Hawaii. Fortunately, a sophisticated Italian lawyer intervened and argued against proceeding with the transaction. [2]

Bengzon, meanwhile, said a Central Bank governor got upset for his sentiments regarding the renewal of the Philippine-US military bases treaty in the early 1990s. [3] He also mentioned that the late president Cory Aquino authorized a backchannel to the US panel during negotiations, a move that undermined Manila's position. [4]

For her part, Evangelista has, arguably, taken a less than candid approach when talking about certain aspects of her work relationships in her book.

She has mentioned Glenda Gloria, executive editor of news website Rappler, several times with fondness and respect.

But she took a different tone when she wrote about Rappler's favorite Nobel Prize Laureate.

Evangelista admitted that she once made "a future Nobel Peace Prize Laureate cry in frustration," obviously referring to Maria Ressa, CEO and founder of Rappler.

"It was my fault," Evangelista said, "but I still say she started it."

A first-person account of this tension convention [5] would have made for a terrific anecdote and, arguably, a more compelling memoir.

Despite the lack of detail regarding this matter, there is no question that Evangelista's writing career is likely to take off further. In short, Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country won't be her last book.

She is young and healthy, allowing her to enjoy international acclaim, a privilege not exactly available to drug war victims she has written about. Most of them have been young once and are now gone but would still be remembered (hopefully), thanks in no small part to her work.

To aid in this remembrance, Evangelista has personally participated in discussions about Duterte's drug war in Quezon City. The event she attended reportedly includes a public reading of book excerpts as well as distribution of donated book copies to members of urban poor communities. [See: Ituloy ang Kwento]

As far as remembering Duterte's slaughter of the innocents is concerned, it is a step in the right direction.

However, despite providing space for truth-telling, the event attended by author (and her book itself) may not easily win the hearts and minds of its target demographic.

It's not difficult to see why.

The intended audience is presumably more familiar with Evangelista, Heart, than the author Evangelista, Patricia (with all due respect to both).

Moreover, the book is written in the language of the elite and the educated (and admittedly, so is this review) and published in an expensive format (an actual book) that is vaguely intimidating to a screen-addicted TikTok user with an attention span shorter than a one-peso wifi access in say, Barangay Tatalon in Quezon City.

But then again, any reporter or author worth their salt will tell you that we all work with what we have.

And this is exactly what Evangelista has done.

Evangelista has put in tremendous effort in covering Duterte's war on drugs and its generally fatal and traumatic effects on its victims.

There is the tough guy and drug addict who is murdered after getting away with feeling up one too many women in his neighborhood.

Another is about an impoverished mother who becomes a victim twice over — the first, after one of her kids becomes collateral damage, and the second, upon finding out too late that her husband has accepted settlement with the accused, a move that went against her wishes.

Evangelista also recounted the experience of fellow journalist Eloisa Lopez.

In 2016, Lopez wept inside a press vehicle after a young man "who looked exactly like what [she] thought an addict would look" was arrested for the rape and murder of a seven-year-old girl. The victim's body was found "with her panties shoved in her mouth."

"Eloisa, crouched on the grimy tile, camera in hand, mouthed the words. Son of a bitch. You fucking son of a bitch. Then she stepped out of the room, walked to the press car, locked the door, and cried," Evangelista wrote.

""That night," [Eloisa] said, "I wanted him to die too.""

Not surprisingly, Lopez's sentiments about drug suspects were shared — at least initially — by three Duterte supporters whose short profiles were featured in the book.

But they were able to redeem themselves later.

When the honeymoon with the Duterte administration was over, all three realized that they were misled by grand theatrics of the Sick Man of Asia.

These and many other accounts are, in equal parts, moving and brutal. They are solid proof that the rest of us are also prone to quick fixes, which the Duterte presidency has employed with murderous intensity.

Meanwhile, in what can be considered as an ironic twist, Evangelista has allotted one full chapter to a police official, a true-blue Diehard Duterte Supporter that — fortunately enough — goes beyond stereotype.

Lt. Col. Roberto Domingo was "good copy," Evangelista wrote, in a chapter entitled My Friend Domingo.

He liked to read, enjoyed the cinema, and is a member of the National Geographic Society, Evangelista added.

Besides being her source, Domingo also becomes something of a friend, thanks to their shared interests in things literary, cinematic, and extra-judicial.

This probably explains why Evangelista allowed him to call her "Trish," even though she introduced herself — and is more popularly known — as "Pat."

But things changed in 2017, the second year of the Duterte presidency.

During that year, Domingo was relieved of duty (although the complaint was dismissed in 2020) after his reported involvement in a scheme that crammed suspects in a secret detention cell the size of a closet.

After the scandal broke out, Domingo called her up, if only to prove his innocence.

""Trish," he began, "you believe me, don't you?"

And with those words, Evangelista promptly ended the chapter, and presumably so did her personal and professional affiliation with a member of Manila's Finest (so-called).

In writing this book, Evangelista was able to put skills, experience, and privilege to good use. She provided color and context to lives she has examined, reminding us that those who were murdered should not have died in vain.

Notes:

[1] Salonga wrote two memoirs: Presidential Plunder: The Quest for the Marcos Ill-Gotten Wealth and The Senate That Said No: The Four-Year Record of the First Post-EDSA Senate. Bengzon, who helped lead the Philippine panel that negotiated the terms of the US military bases treaty renewal in the 1990s, wrote A Matter of Honor: The Story of the 1990-91 RP-US Bases Treaty. (Senator Juan Ponce Enrile also wrote his own memoir but that may be the subject of another blog entry.)

[2] From Page 97 of Salonga's Presidential Plunder: "[Dr. Sergio] Salvioni and the other lawyers made the following summing up: (a) Marcos never intended to pay out any money to the Philippine Government; (b) Marcos agreed with the transfer which [agent] de Guzman attempted to accomplish when he went to the Swiss Credit Bank on March 24 and later on May 6, provided that the transfer was made to the Vienna Bank of de Guzman; (c) Marcos stopped the transfer as soon as he was informed that the destination was changed from Vienna to a Philippine Government account in Credit Suisse in Zurich."

[3] From Page 117 of Bengzon's A Matter of Honor: "...I learned that [Central Bank Governor] Joey Cuisia had called the [Department of Health] looking for me. I called him on a cellphone. He sounded very upset from the start, demanding that I verify whether the papers had quoted me accurately. I said, "Joey," and then chuckled a bit, to try to lighten the atmosphere because he was already very belligerent.

He got more upset, saying: "This is no laughing matter." I said I would recount everything verbatim and did not consider the matter lightly. He said: "I hope you will not back off from a fight which you have started." Now that got me upset, I retorted: "I will not continue this kind of conversation. I will hang up and when you've cooled off, then we can talk again.""

[4] From Page 204 of Bengzon's A Matter of Honor: "[President Cory Aquino] explained how the backchannel began: some months ago, the US had airlifted her Vice-President and political rival Salvador Laurel to a US Navy ship for some closed door discussions. This event had been reported by Louie Beltran in the Philippine Star. President Aquino said that the US government was clearly trying to nurture ties with the Vice-President in the event of her not being able to finish out her term."

[5] The term tension convention was borrowed from one of the novels of Kinky Friedman. [See: Kinky Friedman]